Empowering Low-Power Wide Area Networks in Urban Settings

Abstract

Low-Power Wide Area Networks (LP-WANs) are an attractive emerging platform to connect the Internet-of-things. LP-WANs enable low-cost devices with a 10-year battery to communicate at few kbps to a base station, kilometers away. But deploying LPWANs in large urban environments is challenging, given the sheer density of nodes that causes interference, coupled with attenuation from buildings that limits signal range. Yet, state-of-the-art techniques to address these limitations demand inordinate hardware complexity at the base stations or clients, increasing their size and cost.

This paper presents Choir, a system that overcomes challenges pertaining to density and range of urban LP-WANs despite the limited capabilities of base station and client hardware. First, Choir proposes a novel technique that aims to disentangle and decode large numbers of interfering transmissions at a simple, single-antenna LP WAN base station. It does so, perhaps counter-intuitively, by taking the hardware imperfections of low-cost LP-WAN clients to its . Second, Choir exploits the correlation of sensed data collected by LP-WAN nodes to collaboratively reach a faraway base station, even if individual clients are beyond its range. We implement and evaluate Choir on USRP N210 base stations serving a 10 square kilometer area surrounding Carnegie Mellon University campus. Our results reveal that Choir improves network throughput of commodity LP-WAN clients by 6.84× and expands communication range by 2.65×.

Main content

Recent years have witnessed Low-Power Wide Area Networks (LPWANs)emerge as an attractive communication platform for the Internet of Things (IoT).

Yet, deploying city-scale LP-WAN networks is challenging for two reasons: the density of deployment and the nature of urban environments. First, the sheer density of deployment of LP-WAN nodes means that transmissions from a large number of radios will often collide. Such collisions adversely impact LP-WANs, draining battery life and wasting precious air time and spectrum in a dense network. Second, deployments in urban areas cause the already weak signals of low-power nodes to be further attenuated by buildings and other obstacles before reaching the base station. This greatly reduces the range of LP-WAN sensors from over 10 km in rural areas to 1-2 km or less in urban settings.

At the root of these challenges is the limited capability of LPWAN hardware, both at the base station and clients. On one hand, the limited power budget and low cost of LP-WAN clients make it challenging to deploy sophisticated MAC and PHY-layer schemes to avoid collisions. On the other hand, LP-WAN base stations struggle to resolve a large number of such collisions.

This paper aims to bridge this disconnect – it builds Choir, a solution to overcome the challenges of dense, city-scale LP-WANs despite the limited capability of client sensor nodes and base stations. At the heart of our approach to disentangle collisions at the base station is a strategy that exploits hardware imperfections of low-cost components in LP-WAN radios. Specifically, the signals transmitted by such hardware produces offsets in time, frequency, and phase. Choir proposes algorithms that use these offsets to separate and decode collisions from users. It achieves this by leveraging properties of the physical layer of LoRaWAN LP-WAN radios that transmits signals in the form of chirps, i.e., signals whose frequency varies linearly in time. We show how hardware offsets, whether in time, frequency or phase manifest as distinct aggregate frequency shifts in chirps from each transmitter. We then filter the received signal using these shifts to separate signals from different transmitters. Choir then overcomes multiple challenges to decode useful data packets from each filtered signal component. First, it develops novel algorithms to separate bits of data from hardware offsets, both of which are embedded in frequency shifts of chirps. Second, it uses the precise values of the offsets of the separated signals to identify which bits of decoded data belongs to which client to reconstruct the packet over time.

Beyond dealing with density, we show how hardware offsets between transmissions can boost the range of LP-WANs. Specifically, we consider transmissions from teams of LP-WAN sensors that are individually beyond the range of the base stations, but are physically co-located. Such sensors are likely to record similar readings resulting in overlapping values for the most-significant bits of sensed data. Choir devises a mechanism for such overlapping most-significant bits to be recovered to help obtain a coarse view of sensed data in a given area. We propose a simple modification of the LP-WAN PHY that allows overlapping chunks of bits collected by sensor nodes to be transmitted concurrently as overlapping chunks of signals that are received at higher aggregate power. Choir develops a novel algorithm to achieve this in software without requiring expensive hardware modifications at the LP-WAN clients to tightly synchronize their transmissions.

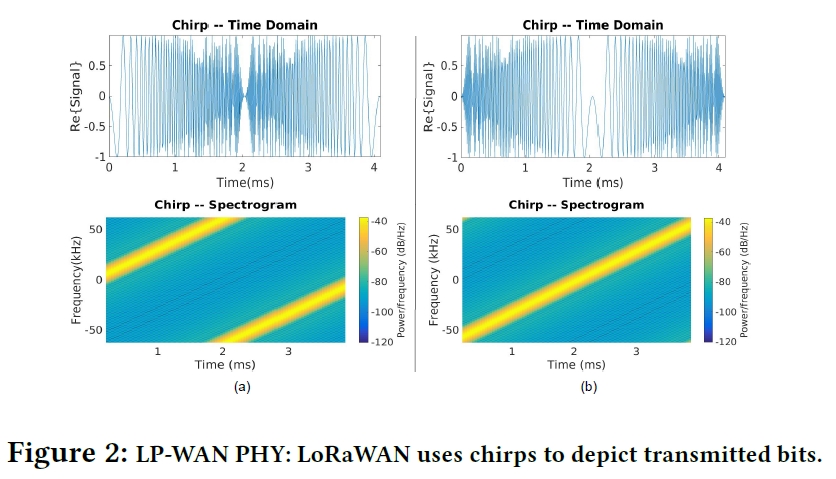

Fig. 2(a)-(b) illustrate two such chirps depicting bits “0” and “1” in the time domain and the corresponding spectrogram. Different bits are encoded by initiating the chirps at different frequencies, for instance “0” at −62.5 kHz and “1” at 0 kHz over a bandwidth of 125 kHz.

The core concepts behind Choir are best understood with an example. Consider two LP-WAN radios, both transmitting the same sequence of n bits to an LP-WAN base station. We assume these n bits are encoded in a single chirp as in Fig. 2 by each transmitter. Suppose the two transmissions are aligned perfectly in time, inducing a collision between their chirps. Given that the two LP-WAN radios encode their bits in the exact same way, the resulting chirps would be identical. At first blush, one would assume that these chirps would combine either constructively or destructively upon colliding. This would be problematic for two reasons: First, the combined signal would be indistinguishable from a single transmitter with higher power, rendering the two chirps from the two transmitters impossible to be separated. Second, if the signals add up destructively, one would not be able to recover either of their transmissions.

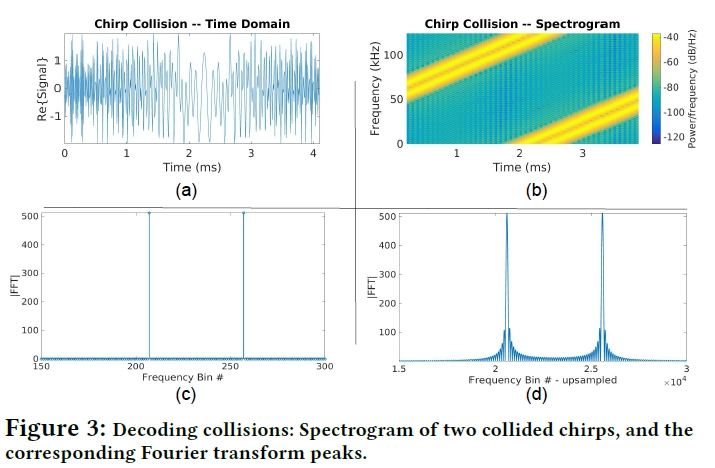

Choir recognizes that in practice, however, the two signals can be separated by exploiting the natural hardware imperfections of the two radios. Specifically, signals from the two transmitters are likely to experience a small frequency offset, due to a difference in the frequency of their oscillators. This would result in the two chirps being slightly offset in frequency. Fig. 3 depicts the spectrogram of two collided chirps from two commodity LP-WAN radios gathered by a software radio. Note that one can observe two distinct chirps that are shifted in frequency, despite the fact that they both convey the same information. At this point, we can separate the two chirps using a simple process: (1) We first multiply the received signal by a down-chirp2 that would result in two tones at two frequencies. (2) We then apply a Fourier transform of size 2n, which results in two peaks corresponding to the two transmissions. In Fig. 3(c), we observe two peaks at two distinct bins, corresponding to the two transmissions. One can then repeat this process for subsequent received chirps to disentangle transmissions from the two users.

While the above approach succeeds in separating the two transmitters, it fails to decode useful data. To see why, recall that Lo- RaWAN encodes data by shifting chirps in frequency. Specifically, n bits are encoded as 2n distinct chirps, each starting at a unique frequency. Consequently, the location of the peak corresponding to each transmitter is given by the sum of this frequency offset and the underlying data transmitted by the user. To illustrate the problem, observe that Fig. 3, has two peaks at bins 207 and 257. Such a collision could both be interpreted as identical data and a frequency offset of 50 bins, or zero frequency offset and encoded data differing by 50 bins, or any of the many options in between.

Choir overcomes this problem by relying on the fact that while frequency offset remains constant over a packet between chirps, data does not. To see how this is useful, consider two packets consisting of three symbols (i.e., three chirps) that collide from two users. We assume that the first symbol is a known preamble shared by all users, while the second and third carry useful data. As a result, peak locations from the first symbol can be used to estimate the frequency offset of the first and second user respectively. These frequency offsets can now be subtracted from peaks in subsequent users to capture data corresponding to the first and second user respectively.

An important question still remains – How do we know who is the first and second user in each data symbol? Knowing this is necessary to map the correct frequency offset to the correct peak. More importantly, it is required to avoid mixing up the data bits of the two transmitters when reporting the decoded data.

Our solution to resolve this challenge relies on the fact that data bits occur on integer peak locations in the Fourier transform, while frequency offsets need not. Put differently, frequency offset is a physical phenomenon and does not need to be a perfect multiple of the size of a Fourier transform bin. As a result, the peak locations can be an arbitrary fraction of a Fourier transform bin. To illustrate, suppose we observe two data symbols where the peaks are at 207.2, 257.6 for the first symbol and 81.6, 200.2 for the second symbol. While the integer parts of these peak locations depend on both data and frequency offset, the fractional part depends only on frequency offset, which remains consistent across symbols. Consequently 207.2 and 200.2 must map to one user while 257.6 and 81.6 belong to the other. Choir therefore can use the fractional part of peak locations to distinguish between peaks corresponding to the different users in each symbol, prior to decoding their data bits. ***

IMPLEMENTATION

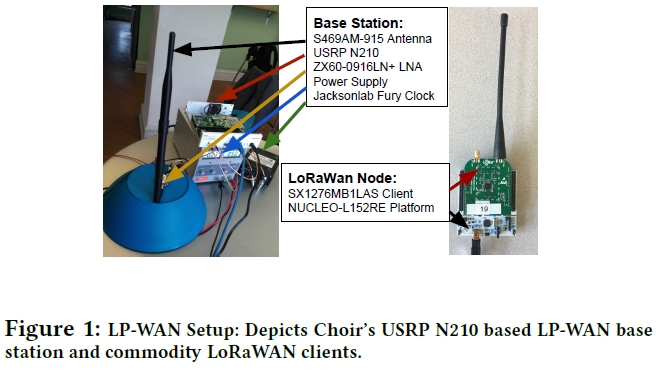

We implement Choir on a testbed of software radio base stations and clients built using commodity components and the LoRaWAN chip. Our base stations are composed of USRP N210 software radios and the WBX daughterboards operating at the 900 MHz bands5.We use the UHD+GnuRadio library and develop our own LoRaWAN decoder and Choir’s algorithms in C++ and MATLAB to process signals. Unless specified otherwise, our base station uses a single S469AM-915 antenna and a ZX60-0916LN+ low noise amplifier. We mounted the base station on the top floors of three tall buildings on CMU campus. Our experiments using MU-MIMO deploy with up to 3 base-station antennas synchronized by a Jacksonlab Fury clock.

The clients are SX1276MB1LAS boards with an embedded Lo- RaWAN chip that is mBed compatible. We connect these boards with NUCLEO-L152RE boards with the mBed platform to program the LoRaWAN chips to transmit sensor data at regular time periods. The boards operate at a center frequency of 902 MHz over a bandwidth of 500 KHz or 125 KHz depending on the data rate the wireless channel supports [5]. We consider three different types of data: (1) Random sequence of bits per packet that are transmitted periodically at regular intervals (500 ms). (2) A specific known sequence of bytes at the same period. (3) Sensor data from temperature and humidity sensors placed across different buildings in the university campus, as they are observed. We leverage an open environmental sensor board platform with an Atmel Atmega32L microcontroller and on-board BME280 temperature and humidity sensors.

Conclusion

This paper presents Choir, a system that improves throughput and range of low-power wide area networks in urban environments. Choir proposes a novel approach that exploits the natural hardware offsets between low-power nodes to disentangle collisions from several LP-WAN transmitters using a single-antenna LP-WAN base station. Further, Choir allows teams of LP-WAN sensor nodes with correlated data to reach the base station, despite being individually beyond communication range. Our system is implemented and deployed on a large outdoor testbed spanning 10 km2 around CMU campus.

Paper

Paper 👉Paper Pages

Video 👉Video