LiveTag Sensing Human-Object Interaction Through Passive Chipless WiFi Tags

Main content

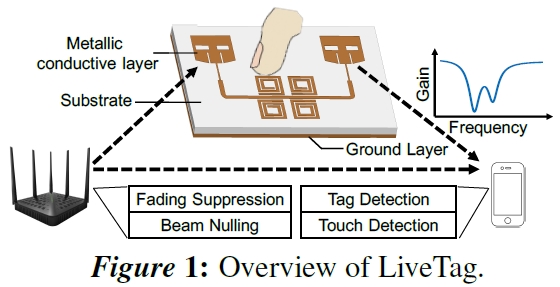

Many types of human activities involve interaction with passive objects. Thus, by wirelessly sensing human interaction with them, one can infer activities at a fine resolution, enabling a new wave of ubiquitous computing applications. In this paper, we propose LiveTag to achieve this vision. LiveTag is a fully passive, thin metal tag that can be printed on paper-like substrates and attached on objects. It has no batteries, silicon chips or discrete electronic components. But when touched by fingers, it disturbs ambient WiFi channel in a deterministic way. Multiple metallic structures can be printed on the same tag to create unique touch points. Further, LiveTag incorporates customized multi-antenna beamforming algorithms that allow WiFi receivers to sense the tag and discriminate the touch events, amid multipath reflections/interferences. Our prototypes of LiveTag have verified its feasibility and performance. We have further applied LiveTag to real-world usage scenarios to showcase its effectiveness in sensing human-object interaction.

The system should be inexpensive for ubiquitous deployment, and should be unobtrusive— always functioning but without distracting users and with little maintenance cost. In addition, it should preserve privacy, capturing nothing more than the user’s interest.

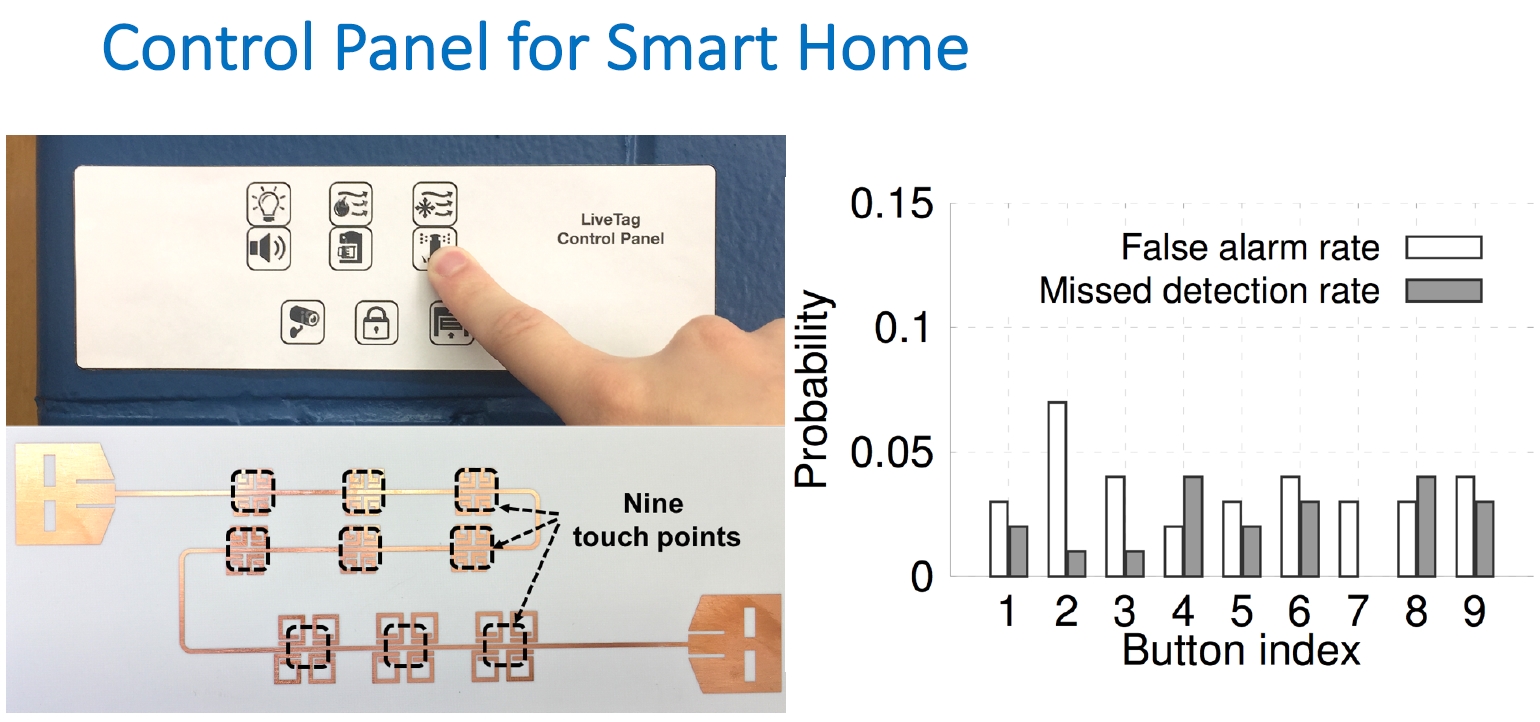

LiveTag uses thin radio-frequency (RF) tags as a user interface, either attached on the objects, or working independently as a thin keypad or control panel.

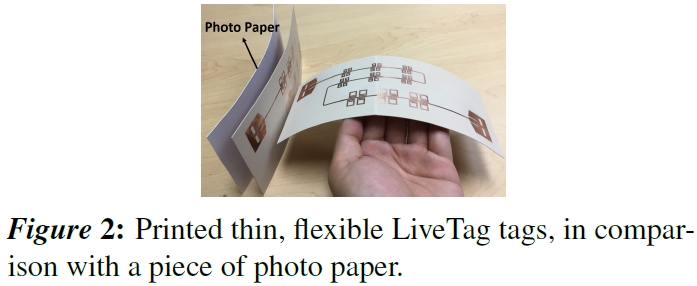

These tags are fully passive, chipless, and battery-free, only made of a layer of metal foil printed on a thin substrate (e.g., flexible ceramic-PTEF laminate commonly used for thin PCB printing, as shown in Fig. 2). Touch commands on the tags are detected remotely by WiFi devices which can react accordingly. More specifically, the tag is designed as a strong reflector for 2.4/5 GHz signals from a cooperating WiFi transmitter, and touches upon its metal structure create a known non-linear channel distortion which can be remotely detected by a WiFi receiver.

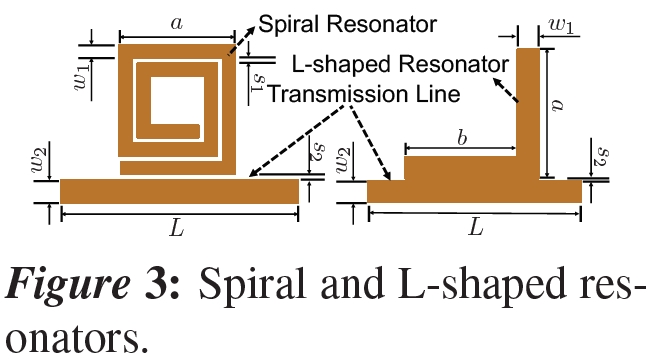

To satisfy the targeted use cases of LiveTag, the tags need to be sensitive to WiFi signals, contain multiple distinguishable touch points, and bear identifiable characteristics. In meeting these requirements, we create RF surface capacitors/inductors/resistors by printing metal structures with special geometries. These surface electronic components eventually form a resonator that absorbs WiFi signals of specific frequency, acting like a bandstop filter to create a “notch” on the WiFi channel response. Multiple resonators can be co-located on the same tag with different notch positions. Together, these resonators create a spectrum signature that makes the entire tag uniquely distinguishable from others. In addition, finger touch on each resonator nullifies the notch, resulting in a unique change in the WiFi channel response.

Under controlled setup where the signals directly pass through the tag, we observe up to 35 dB of attenuation at the desired notch points.

Chanllenge:

First, the line-of sight (LOS) channel between the WiFi transmitter and receiver is much stronger and can easily overwhelm the signals reflected by the tag.

Second, due to frequencyselective fading caused by ambient multipath reflections, the spectrum signatures tend to be interfered by random channel gain variations across the frequency band. Multipath fading produces Notch. It makes it mix with the notch of the tag.

Solution

We use beamforming technology to know the direction of the LOS and use the nulling mechanism to eliminate the interference.

We use the beamforming technique to know the notch in different directions, and the notch obtained by the tag will always exist to determine the notch we want.

To tackle such uncertainties, we design redundancies into the tag and combine multiple resonators to enhance the spectrum signature. To enable robust detection, we design a fading suppression and LOS nulling mechanism, taking advantage of the multiple antennas on the WiFi transceivers. The touch event is then detected as a known change in the spectrum, following a stochastic model that guarantees a prescribed false alarm rate.

Our experiments in practical indoor scenarios demonstrate that both the presence of and touch upon a multi-resonator tag can be detected accurately, even when the tag is placed 4.8m away from the transmitter. The miss detection rate(Pm) and false alarm rate (Pf ) is only around 3%, and approach 0 with multi-resonator redundancy. The tag-to-receiver distance needs to be shorter (around 0.5 m).

Contributions

In summary, the main contributions of LiveTag include: (i) Tag design. Although the concept of passive RF tags has existed for long, existing designs mainly focused on manipulating the tag signatures to embed more information, and they need dedicated ultra-wideband, fullduplex readers. To our knowledge, LiveTag represents the first system to design touch-sensitive,WiFi detectable tags that can sense human-object interaction.

(ii) Tag detection. We design new beamforming mechanisms to suppress ambient multipath and LOS interference, enabling a pair ofWiFi Tx/Rx to detect the passive tag and multipoint touch events in practical environment.

(iii) Implementation and experimental validation. We implement the tags using standard PCB printing technique (which allows mass production and tag customization). Our experiments verify LiveTag’s feasibility and accuracy, and its usefulness in enabling new sensing applications that involve human-object interaction.

When the interrogation signal reaches the tag, it is first received by one antenna, and then passed through a transmission line and filtered by a multi-resonator network. The resulting signal is eventually emitted through the other antenna.

The resonator is essentially a 2D bandstop filter printed on a planar substrate.

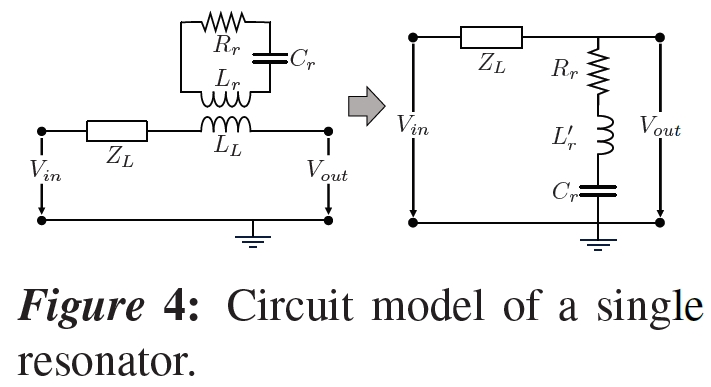

The resonator can be modeled by an equivalent circuit (Fig. 4), comprised of a cascade of capacitor Cr, inductor Lr, and resistor Rr, whose values are determined by the resonator’s material and geometry.

On the other hand, the frequency response of each resonator is determined by three factors: the substrate, material of the conductive layer, and the resonator’s geometry, which we elaborate on below.

Material of substrate and conductive layer.

Live-Tag adopts either the woven glass (FR-4) or ceramic-PTEF flexible PCB as substrate. The thickness and dielectric constant of substrate affect the center frequency of the stopbands.To isolate the tag from other objects behind, we ground the tag by printing a thin copper layer on the back of the substrate. The conductive ground layer shields the EM wave from external materials behind the tag.

Impact of the resonator’s geometrical parameters.

The line length (L) only affects the phase of the EM wave, and does not impact the spectrum signature which only concerns the magnitude of the CSI. Therefore,

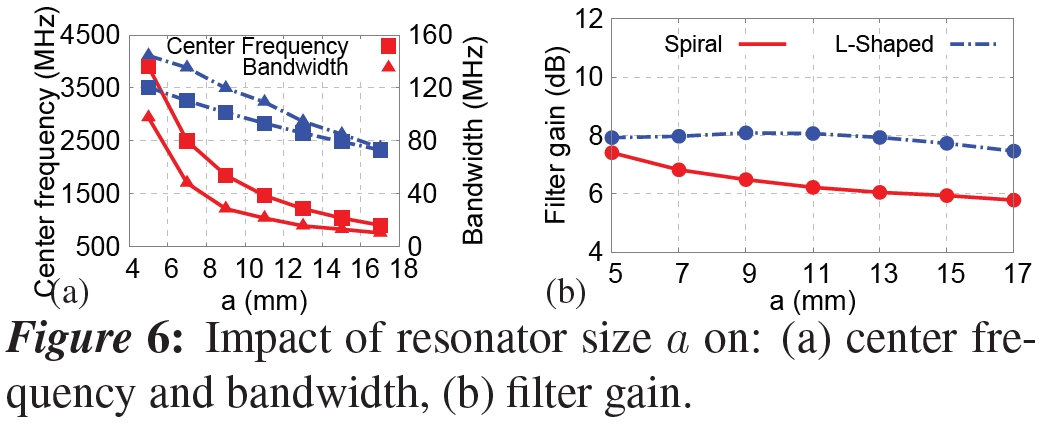

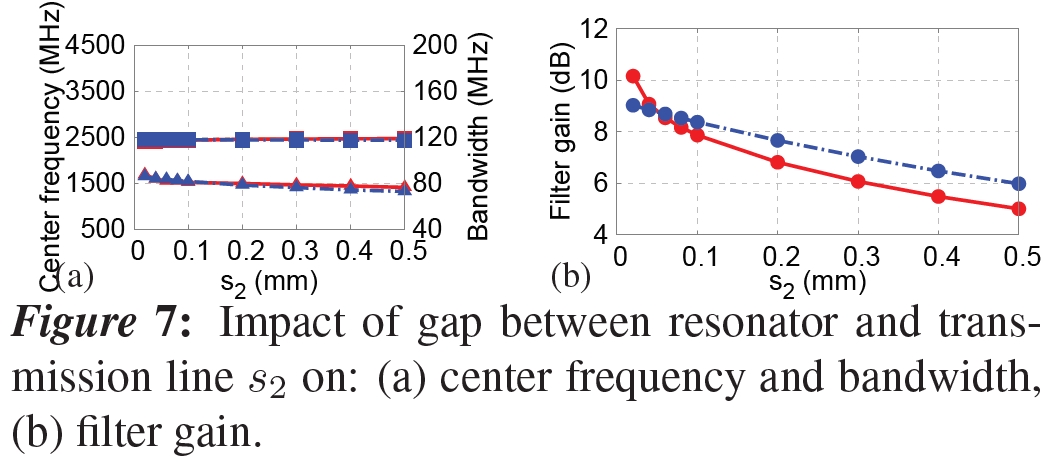

Our simulation results in Fig. 6(a) indicate that a larger resonator leads to lower resonance frequencies, because it increases the wavelength of the standing wave. so a larger a (and hence larger L0r) decreases the bandwidth of the notch. Fig. 6 (b) further shows that the resonator size does not affect the filter gain significantly.

On the other hand, as s2 increases, the coupling between the resonator and the transmission line weakens, resulting in less signal energy being passed to the resonator, and hence a sharp reduction in the filter gain, as shown in Fig. 7 (b).

Under the same simulation setup, we also found that the other parameters, w1, s1, Nt and b (Fig. 3), have negligible impacts on the frequency response.

To summarize the foregoing exploration, the resonance frequency can be controlled by adjusting the resonator size, while the gap between resonator and transmission line should always be kept as small as possible to achieve a high filter gain and small bandwidth occupation

a finger touching the resonator can be approximated as adding a capacitor and a resistor in parallel to the original resonator’s components, and then to the ground. This leads to an equivalent increase of Cr, thus making the notch’s center frequency disappear from its original position.

To create multiple touch points, we extend the single-resonator design by placing multiple resonators with different resonance frequencies along side the transmission line. In addition, we place multiple identical resonators with the same resonance frequency close to each other, to form a compound touch point.

Evaluation

Case

Advantage

- The author proposes a new idea for batteryless, chipless and low-cost wireless human-computer interaction, and uses the original WIFI signal in the home as the transmission signal.

Weakness

- The Tag and Receive distances are close because multipath fading and self-interference are not well handled.

- When Receive moves, the device may not work due to self-interference.

- Transmitter to Tag and Tag to receive distance are close.

- The author puts forward particularly good ideas and cases, but does not substantially solve the existing problems. The author’s method is very limited and not practical for the use of the scene.

Paper

Paper 👉Paper Pages

Slide 👉Slide Pages

Vedio 👉Vedio