Energy Harvesting and Wireless Transfer in Sensor Network Applications:Concepts and Experiences

Main content

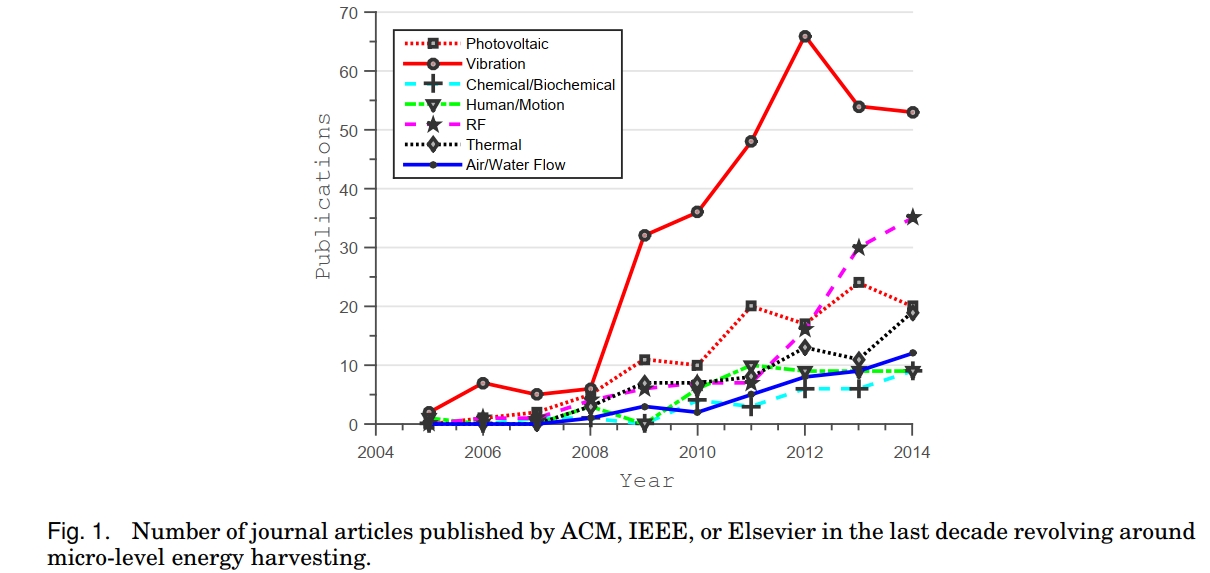

This article discusses these aspects by surveying paradigmatic examples of existing solutions in both fields, and by reporting on real-world experiences found in the literature. The discussion is instrumental to providing a foundation for selecting the most appropriate energy harvesting or wireless transfer technology based on the application at hand.

Wireless energy transfer (WET)—that is, the ability to move energy across space—can break such coupling, allowing WSN designers to exploit abundant energy sources available at places other than the locations of sensing. In addition, WET may distribute the available energy from energy-rich locations to energy-poor ones, improving the overall energy balance.

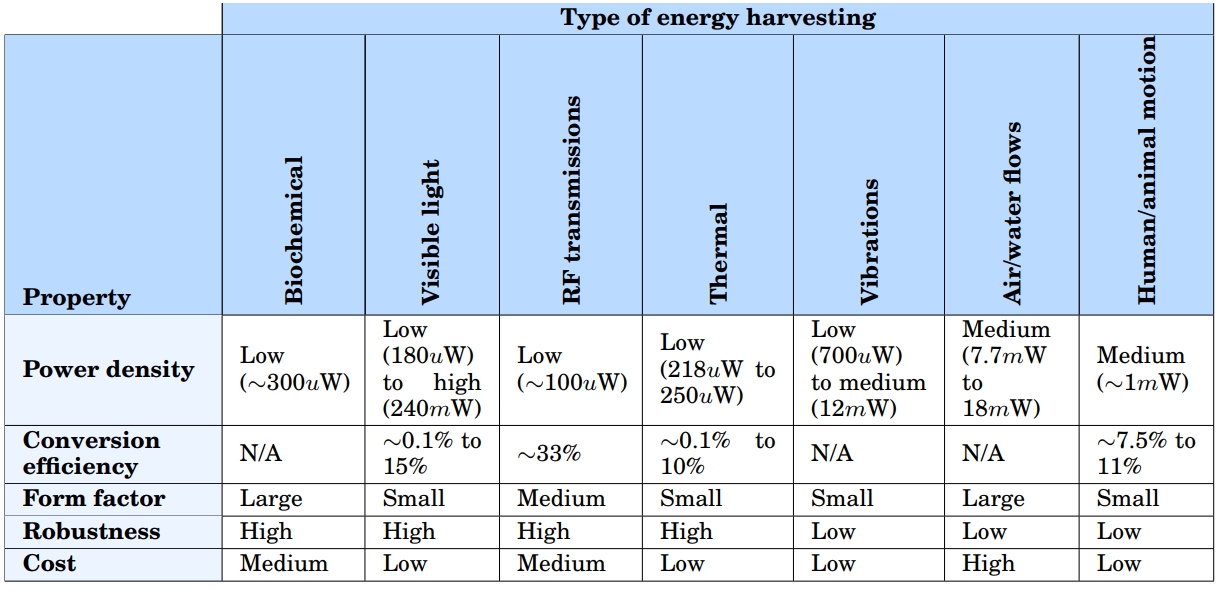

Energy harvesting solutions should present a set of desirable properties:

- EH1 : high energy density. Sources should bear an intrinsically high energy content; because of the limited efficiency of current extraction techniques, harvesting is useful only whenever the energy density of the source can compensate it.

- EH2 : high efficiency. To justify the added system complexity, a certain extraction technique should be able to take out the highest possible fraction of the energy density offered by a given source.

- EH3 : small form factor. The extraction technique should operate at micro-level and the harvesting device be realizable in small form factors, ideally at most on the scale of the WSN node, not to complicate the deployments.

- EH4 : high robustness. The harvesting equipment should be sufficiently reliable and require limited maintenance, even if exposed to stressful environmental phenomena; ideally, it should not further constrain the WSN lifetime.

- EH5 : low cost. The harvesting equipment should be attainable at low cost, not to significantly impact the system’s total cost of ownership.

kinetic Energy

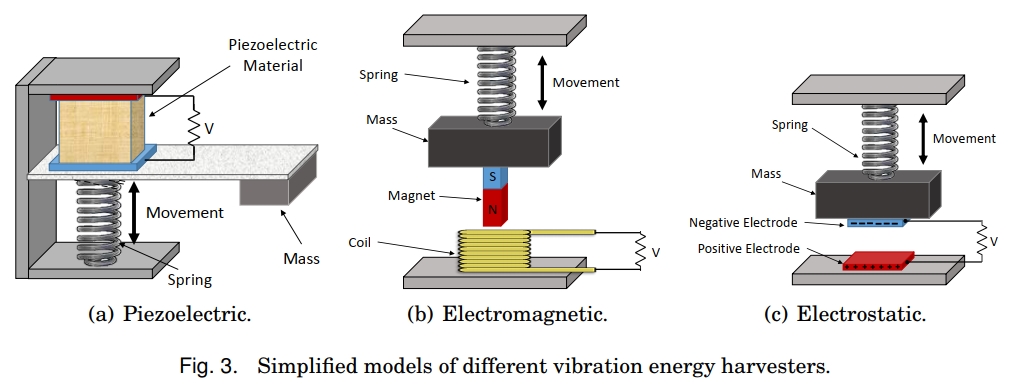

Piezoelectric effect

Whenever a piezoelectric material is put under some external force, it causes a deformation of the internal molecular structure that shifts positive and negative charge centers. This produces a macroscopic polarization of the material directly proportional to the applied force. The resulting potential difference across the material generates an alternating current (AC), which is then converted into direct current (DC). The choice of piezoelectric material greatly influences the harvesting efficiency. One of the most commonly used materials for piezoelectric energy harvesting is Lead Zirconate Titanate (PZT), which is however brittle in nature and susceptible to cracks upon high stress. Another commonly used material is Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF), which is comparatively more flexible than PZT. Although PZT and PVDF are capable of generating high voltage, the output current is low due to their high impedance, thus limiting the harvesting efficiency.

Electromagnetic and electrostatic effects

To produce the change in the magnetic conditions around a coil, a magnet acts as the mass in a mass-spring system that produces movement parallel to the coils axis. In the case of mass-spring systems, besides the magnet’s mass, its material and the coils characteristics concur to determine the efficiency of the harvesting device. Most solutions use Neodymium Iron Boron (NdFeB) for the magnet, as it provides the highest magnetic field density. Although electromagnetic generators are more efficient than piezoelectric ones, their fabrication at micro level is difficult:the assembly is complex and care must be taken to align the magnet with the coil.

Differently, electrostatic transducers produce electric energy due to the relative motion of two capacitor plates, as in Figure 3(c). When the ambient vibrations act on a variable capacitance structure, its capacitance starts oscillating between its maximum and minimum values. An increase in the capacitance decreases voltage and vice versa If the voltage is constrained, charges start flowing towards a storage device, converting the vibration energy into an electrical one.

RADIANT SOURCES

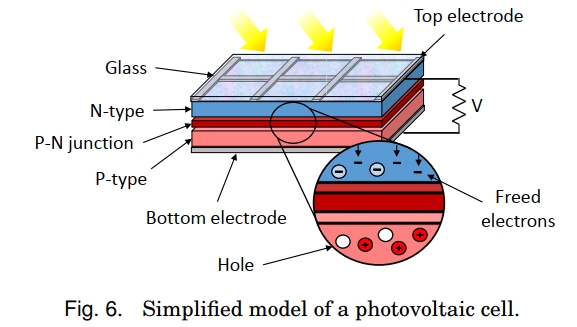

Extracting Energy from Visible Light

Photovoltaic cells, leveraging the photoelectric effect, are one of the most mature energy harvesting technologies. When light hits the N-type layer, due to the photoelectric effect, the material absorbs the photons and thus releases the free electrons. The electrons travel through the P-N junction towards the P-type layer to fill the holes in the latter. Among the freed electrons, few of them do not find a hole in the P-type layer, and move back to the N-type layer. This occurs through an external circuit, whereby the generated current is directly proportional to the intensity of light. Thus, photovoltaic cells are generally modeled as current sources.

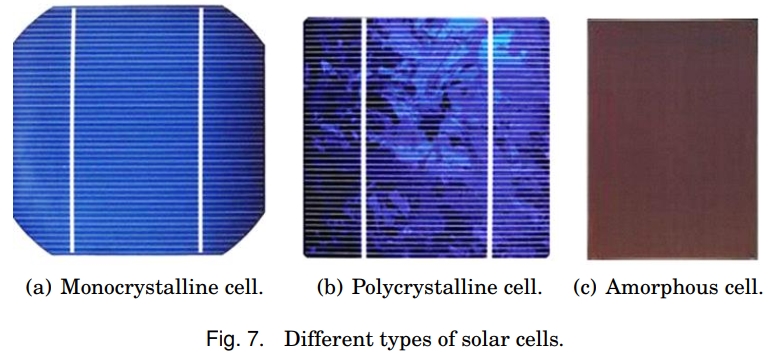

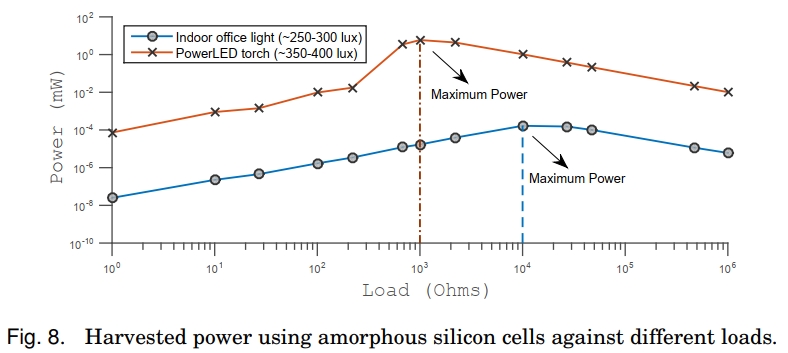

The material used in a cell’s construction mainly determines its efficiency. Figure 7(a), use a single crystal of silicon, and are both most expensive and most efficient. However, they are not employed at micro level because of their cost. Polycrystalline cells, shown in Figure 7(b), use multiple silicon crystals and can be recognized by their shattered-glass look. They are less efficient than monocrystalline cells, but their lower cost outweighs the efficiency losses. Amorphous silicon cells—also known as thin film cells, shown in Figure 7(c)—are manufactured by depositing vaporized silicon on a substrate of glass or metal and may be flexible, which simplifies installation. These are both the least performing and cheaper type of cell; however, under typical indoor lighting conditions, they may outperform monocrystalline ones.

Extracting Energy from Radio-frequency (RF) Transmissions

The key element of an RF energy harvesting device is the “rectenna”, that is, a special type of antenna able to convert the energy carried by electromagnetic waves directly into electrical current. A rectenna comprises a standard antenna and a rectifying circuit. The antenna captures the electromagnetic waves in the form of AC current; the rectifier performs the AC-to-DC conversion, making a rectenna resemble a voltagecontrolled current source.

THERMAL SOURCES

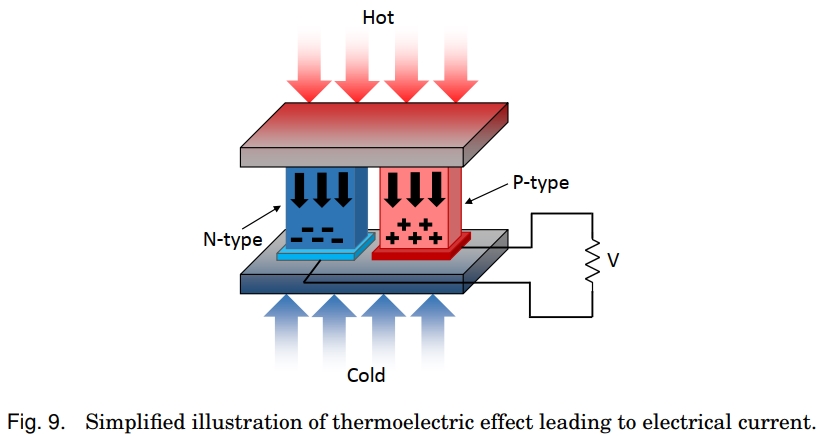

Whenever the conditions of thermodynamic equilibrium cease to exist, the resulting matter or energy flows become usable to harvest electric energy through thermoelectric or pyroelectric techniques. Thermoelectric techniques are based on Seebeck’s effect, which is conceptually similar to the photovoltaic techniques. N-type and P-type materials are employed here as well, as shown in Figure 9. As the temperature difference between opposite segments of the materials increases, charges are driven towards the cold end. This creates a voltage difference across the base electrodes, which is proportional to the temperature difference. Silicon wafer or aluminum oxide are typically used as a substrate material, because of their large thermal conductivity. pyroelectric energy harvesters leverage materials with the ability to generate a temporary voltage as their temperature is made continuously varying, much like piezoelectric materials generate a potential when they are distorted.

BIOCHEMICAL AND CHEMICAL SOURCES

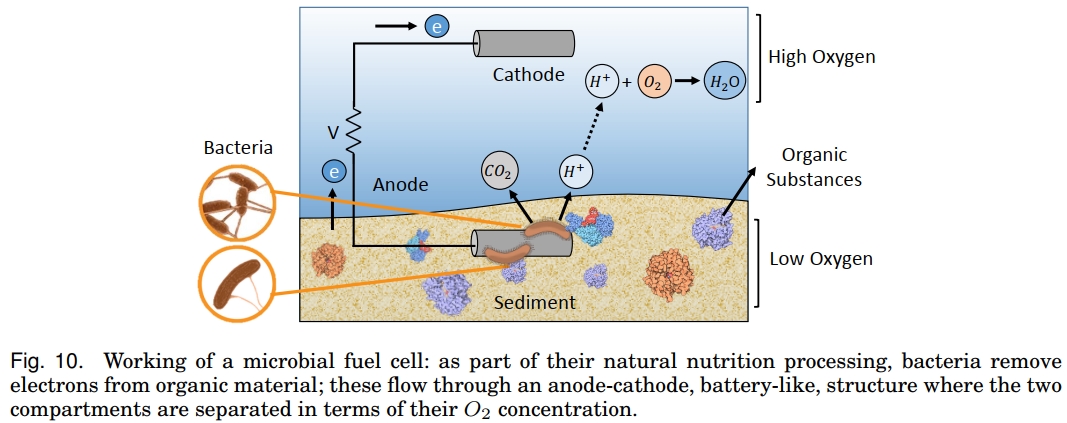

Energy harvesting may leverage forms of biological or chemical energy in specific environments.Among biochemical extraction techniques, microbial fuel cells (MFC) use biological waste to generate electrical energy, as schematically shown in Figure 10. The efficiency of an MFC is thus a function of the difference in oxygen concentration across the anode and the cathode sections. This is why, for example, MFCs deployed in marine environments have the anode partly embedded in soil and the cathode placed close to the surface, at a higher oxygen concentration, as in Figure 10.

Extraction techniques based on chemical processes typically focus on taking advantage of corrosion phenomena; for example, those occurring on steel bars used to reinforce concrete structures.

Paper

Paper 👉Paper Pages